Orbán Unplugged: How a Battery Boom Backfired on Illiberalism

Viktor Orbán’s industrial policy derisked foreign investment in lithium batteries. Instead of cementing his rule, it’s now tearing it apart.

Debates on financing industrial policy often focus on fiscal sustainability in advanced economies. But Hungary’s industrial policy in electric batteries reveals deeper political liabilities in semi-peripheral states. Acting as a bridge between Chinese and Western capital, the Hungarian government’s measures to anchor investments by German carmakers and Asian battery giants have triggered cascading blowback across political institutions, public finances, and civil society—threatening the stability of Orbán’s entrenched power system.

Orbán’s Political Support in Freefall

Viktor Orbán’s political survival is jeopardized for the first time in over a decade. According to polling data published on 10 April 2025, the opposition’s Tisza Party leads Orbán’s Fidesz 34% to 28% among the general population—and by a striking 51% to 37% among likely voters with established party preferences [1]. The shift is all the more remarkable because nobody had heard of Tisza before March 2024, when Péter Magyar, a former insider within Orbán’s regime, broke ranks to create a movement uniting disaffected Fidesz conservatives with liberal and even left-leaning voters. Orbán's Orwellian "regime of national cooperation" (NER in Hungarian) seems unable to contain the wildfire of discontent.

Long dulled by the NER regime’s dominance over a divided opposition, Hungarian politics has suddenly come alive. Much of the current media coverage frames this as a personal duel between Orbán and Magyar, concealing how the political drama is also tethered to the regime’s industrial policy. This is a story of how Orbán’s bid to cement his regime by making Hungary into a key site of lithium battery manufacturing backfired spectacularly. To understand why batteries are crucial for Orbán, but also why the lithium battery gamble destabilized his own regime, it helps to situate Hungary’s battery boom within the troubled arc of its FDI-dependent, export-led growth model.

The NER Regime’s Golden Age: 2010-2022

After the collapse of state socialism in 1989, successive governments embraced privatization and low wages to attract foreign direct investments (FDI), but for many, this meant deindustrialization, mass unemployment, and deep social dislocation [2].

Rising to power in 2010 amid the wreckage of a foreign currency mortgage crisis that devastated Hungarian households [3], Orbán promised to challenge foreign capital dominance. In practice however, he lacked both a robust national bourgeoisie or the fiscal space to confront multinationals, while the European Commission and bond markets wouldn’t have tolerated a frontal assault on foreign investors’ property rights.

So instead, Orbán engineered a dual economy. On one hand, he courted German carmakers—the backbone of Hungary's export sector—with Europe's lowest corporate tax rate and business-friendly labor reforms. On the other, he incubated a domestic oligarchy in non-tradeable sectors through state patronage, biased public procurement contracts, diverted EU funds, and subsidized lending. This cemented a dual economy: globally integrated multinationals in export-driven, capital-intensive manufacturing, and domestically oriented Hungarian capitalists reliant on state patronage and rents. The two groups were sufficiently insulated to prevent conflicts, while Orbán positioned himself as indispensable to both.

For a decade, this system delivered political stability. The government absorbed unemployment through public works programs while pacifying middle-class homeowners and SMEs through subsidized lending [4]. Fiscal conservatism—including a German-inspired debt brake—kept bond markets and Brussels temporarily at bay [5].

By 2022, however, the model was facing new threats. Orbán’s consolidation of power hinged not only on subverting EU funds and controlling the circuit of credit, but also on bringing nominally independent institutions—such as the public media, civil service, regulators, the Central Bank, and the judiciary—under tighter political control. Years of documented rule of law violations and misappropriations of EU funds eventually prompted a reluctant European Commission to freeze €30bn in EU transfers— a vital source of rents for the regime. Meanwhile, Russia's invasion of Ukraine triggered twin shocks: surging energy prices strained Hungary's balance of payments, while global interest rate hikes ended the era of cheap money which had underpinned the regime's financial pacification strategy.

As Orbán's economic balancing act faltered, a pivot to electric vehicle (EV) and lithium battery manufacturing emerged as his new gambit — a last-ditch effort to align his political survival with the interests of German carmakers and domestic capitalists.

Hungary Becomes a Lithium Battery Powerhouse

Even before Orbán’s political fortunes waned, his government was already planning to shore up a fledgling battery sector to safeguard Hungary’s main growth engine: an automotive industry dominated by local subsidiaries of German carmakers (OEMs), which employs 175,000 people, while generating 5% of GDP, and over a fifth of exports [6].

The push was triggered by Brussels, as a 2014 EU Regulation set a fleet-wide emissions cap of 95g CO₂/km for European carmakers by 2021, making investment in internal combustion engines uneconomical and accelerating the European car industry’s shift to electric vehicles (EVs). For Hungary’s export-led growth model, the transition to EVs posed an existential threat: lacking comparative advantages in electromobility, the government feared German OEMs would relegate Hungary to assembling the last generation of ICEs while shifting EV production to more R&D-rich countries.

To avoid a rupture in its vital export sector, Budapest aimed to become indispensable to the German auto sector’s electric future. By 2016, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Hungarian Investment Promotion Agency (HIPA) were aggressively courting Asian battery manufacturers to anchor gigafactories near German OEM sites.

The strategy exceeded all expectations: South Korean, Japanese, and Chinese battery makers poured in, triggering an FDI chain reaction as they also brought their home suppliers of cathodes, anodes, and separators in a process known as follow sourcing. Between 2016 and 2025, 43 Asian firms across the lithium battery supply chain announced investments in Hungary: the rapid consolidation of the battery ecosystem convinced car OEMs to retrofit their existing plants or create dedicated EV production sites.

Overall, the battery-EV nexus has attracted more than €20 billion worth of investments [7]. Chinese investments were particularly striking [8]: after CATL unveiled a €7.3 billion plant in Debrecen and BYD announced a €5 billion EV factory in Szeged, Hungary suddenly became Europe’s top destination for Chinese FDI, attracting 44% of all Chinese investment into the continent in 2023 [9].

For an interactive map of the battery value chain in Hungary, click on the picture:

In a forthcoming study, Vilmos Weiler outlines four key advantages the battery bonanza delivered to the NER regime [10]:

[1]. It preempted the risk of OEM divestment from Hungary as German carmakers retrofitted their existing ICE plants or created new ones entirely dedicated to EV models

[2]. FDI inflows helped with the macroeconomic stabilization of a dependent export-led growth model that is structurally reliant on foreign capital transfers, especially in the context of dwindling EU transfers (the graph below illustrates how FDI inflows temporarily offset the current account shock and decreasing EU transfers)

[3]. Building the infrastructure necessary for the battery ecosystem created new rentier opportunities for the Hungarian crony capitalist class

[4]. Towering Chinese FDI helped anchor the NER regime’s geoeconomic ambitions to use the opportunity structure of the US-China cold war to position Hungary as a strategic site connecting Western and Chinese capital groups, playing the role of a connector economy mediating between adversarial blocs – a role it has effectively played since WWII [11]

Source: MNB Balance of Payments Time Series (Hungarian Central Bank)

The Macrofinancial Costs of Derisking the Battery-EV Nexus

Hungary’s rapid battery buildout was meant to bolster the NER regime, but it exposed unexpected macrofinancial and political vulnerabilities. One key liability was exposure to the ripple effects of great power industrial policies as global markets for EVs, batteries, and critical raw materials are ultimately shaped by the strategic decisions of the world’s wealthiest states.

Germany’s sudden EV subsidy cuts in 2023 thus triggered a 69% collapse in domestic sales by August and contributed to a 3% drop across Europe in 2024 [12]. In Hungary, the battery sector hit an overcapacity crisis: by December 2024, output plunged 51%, gigafactories shed 3,000 jobs [13], and utilization fell to 30–40% [14].

But the deeper strain lay in the costs of derisking the battery sector. Hungary committed €3.8 billion in subsidies to battery manufacturers and their suppliers [15] —2% of GDP and 3% of public debt—an extreme case of the derisking model described by political economists Daniela Gabor, Benjamin Braun, and Brett Christophers [16] whereby states absorb private investment risk onto their balance sheet.

This, however, was only the tip of the derisking iceberg: lacking the infrastructure, energy capacity, and labor necessary for hosting a battery ecosystem, the government assumed the costs of derisking an entire regime of production. Energy price volatility proved especially dangerous. With Hungary’s low-cost manufacturing model at risk after the energy price spikes of 2022, Budapest shielded investors and households by absorbing €8.4 billion in energy costs—equivalent to 1.8% of the combined Hungarian GDP over 30 months [17].

Source: European Commission

The combined costs of derisking the battery sector and surging energy prices after the 2022 inflation shock sharply worsened Hungary’s macrofinancial position: the current account balance fell to -8.5% of GDP in 2022, the fiscal deficit hit 6.7%, 10-year bond yields rose to 7.6% in 2023, and the forint weakened 13.7% against the euro between January 2022 and January 2025.

Source: FRED, ECB

This leaves the NER regime in a bind. To win the 2026 election, Orbán would need looser fiscal and monetary policy to shower money on electorally salient groups. Yet public finances and high interest rates tie his hands. After years spent lowering public debt to increase his autonomy from the EU, IMF, and bond markets, Orbán now faces a stark choice: austerity that risks his re-election, or fiscal loosening that might provoke a backlash from Brussels and bond markets. The European Commission already launched an Excessive Deficit Procedure on 26 July 2024, forcing Budapest to freeze €10 billion in planned investments in infrastructure and healthcare. The growing tension between the regime’s political needs and the state’s macrofinancial balance has triggered high-level clashes within the regime, culminating in the replacement of the Central Bank’s leadership with extreme Orbán loyalists in early 2025.

Critics of the Battery Sector Unite

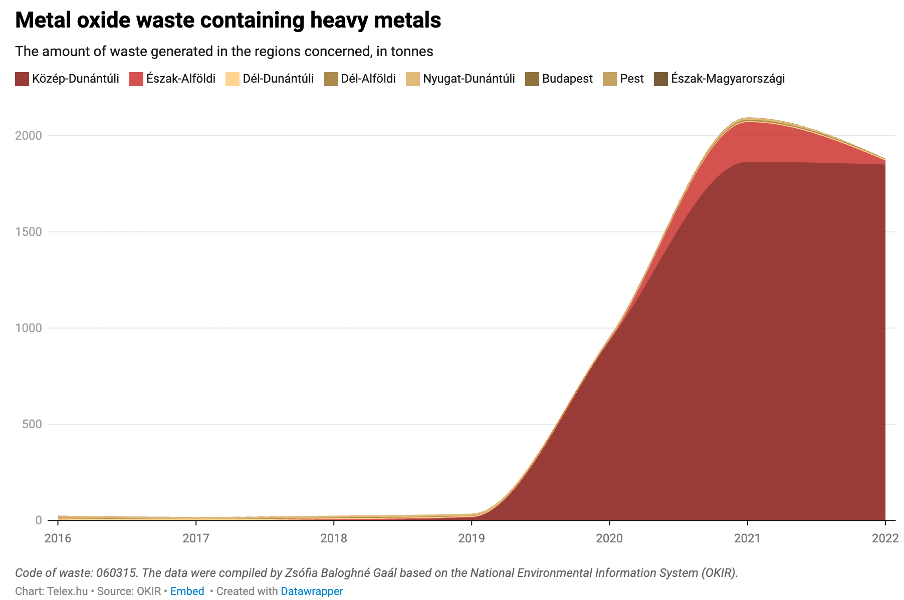

Alongside the hefty price tag, Hungary’s battery boom also burned precious political capital, alienating constituencies concerned with environmental degradation, reliance on foreign labor, and the centralization of state-managed rents. The rapid scaling of battery manufacturing has dramatically increased toxic waste, outpacing recycling and regulatory capacity.

Source: Telex/Masfelfok [18]

Source: Telex/Masfelfok [19]

Near the city of Debrecen, where CATL is building a €7.3 billion gigafactory, local residents launched the grassroots movement “Mikepércs Mothers for the Environment” to protest water and air pollution. North of Budapest, the “Göd-ÉRT” association opposes pollution linked to Samsung SDI’s factory. In 2023, investigative journalism platform Atlatszo sued the national environmental agency for failing to disclose the levels of toxic materials recorded in the groundwater near Samsung’s gigafacory; when the agency finally complied, it emerged that no samples had ever been taken [20]. Fines on battery makers remain minimal, amid reports of political pressures on regulatory authorities to spare firms.

The government’s failure to conduct environmental impact assessments or consult residents has fed a perception that it is sacrificing public health for foreign capital. The optics are damaging for a government which built its entire identity around economic sovereignty. Townhall meetings on battery plants regularly devolved into chaos, as Fidesz-linked officials failed to calm public anger [21]. A 2023 initiative by green opposition party LMP to hold a national referendum on battery factories was blocked by the Electoral Commission. Debrecen—a longtime Fidesz bastion—offers a snapshot of the backlash: the Fidesz-aligned local mayor’s support fell from 61.84% in 2019 to 48.39% in 2024, largely due to local battery plant opposition. By early 2025, new alliances were forming: the “Mikepércs Mothers for the Environment” and the Tisza Party held a joint protest against battery manufacturing and the city’s Fidesz leadership [22].

A second major fault line is labor. Experts broadly agree that Hungary’s battery boom generates mostly low-wage assembly jobs, without technology transfers to local firms and no path to upgrading—only deeper structural dependency on foreign capital [23[. Public backlash has focused on two fronts: poor workplace safety and non-EU temp workers. Workplace safety became a flashpoint after multiple accidents [24]. Between 2022 and 2023, three workers died at SK On’s battery plant. In May 2023, 14 more fell ill after inhaling toxic metal oxides. At SungEel’s recycling facility, 18 workers were exposed to hazardous particles, and inspectors found nickel levels 2,000 times above the legal limit. The plant was shuttered temporarily when inspectors themselves had to be hospitalized.

The industry’s reliance on non-EU temporary workers proved even more damaging for the regime. Orbán’s post-2015 messaging made xenophobia a central theme, warning of a “great replacement.” But with labor shortages forecast to hit 300,000 by 2030 [25], the government struck biletaral deals with countries such as the Philippines, Indonesia and Kyrgyzstan to bring in temporary guest workers— strictly barred from residency or family reunification. Of the 30,000 workers in the battery sector, 3,000 to 5,000 are non-EU temporary workers [26]. While small in number, their visibility has magnified the contradictions between the regime’s nationalist xenophobia, and its reliance on Global South workers in a sector entirely controlled by foreign multinationals.

Thirdly, the pivot to electric batteries has gone hand-in-hand with a reduction and concentration of rents. Due to poor local R&D and innovation, domestic capitalists are unable to meaningfully participate in the battery and EV ecosystem. The main tangible benefits for them are public procurement contracts to supply the built infrastructure necessary for foreign manufacturers. While infrastructure gaps in the EV sector create lucrative rentier opportunities—contracts upwards of €500mn for Orbán’s inner circle—the overall pool of rents has shrunk and become tightly controlled. The tsunami of FDI in the battery supply chain—estimated at €21.6 bn between 2020 and 2025—still doesn’t offset the €30bn in frozen EU funds, previously central to the regime’s patronage model. Rents have become so centralized that four oligarchs dominate all major battery-related infrastructure development projects, with Lőrinc Mészáros, the regime’s foremost oligarch, securing 80% of this market.

Source: Compiled by author based on Hungarian Official Procurement Records and Press Investigations (2023–2025)

The battery boom may have opened new rentier channels, but their narrow concentration leaves much of society untouched by the FDI surge. As rents contract and consolidate, Orbán can no longer rely on the automatic loyalty of a rent-dependent class of domestic capitalists. Fractures in the power bloc are now fuelling support for the Tisza party, which has built its campaign on anti-corruption.

Magyar’s supporters illustrate a heterogenous mix of entrepreneurs at odds with the regime, business executives and Fidesz defectors: The owner of a fertilizer conglomerate on the brink of bankruptcy due to punitive fines issued for price fixing by the Competition Authority [27], the former CEO of sporting goods retailer Decathlon’s Hungarian subsidiary [28], the former Head of the Hungarian Olympic Committee [29], or the former Chief of the General Staff of the Hungarian Defence Forces [30]. Rumours persist that György Matolcsy, former Governor of the Central Bank and erstwhile macroeconomic architect of the NER regime, has recently also made overtures to Magyar [31].

Orbán’s Battery Empire on a Path to Strategic Cell-Mate

The NER regime is clearly at a crossroads: one path forward might see an escalation of authoritarian repression following Erdogan's playbook — Magyar and the Tisza party might for instance be barred from the 2026 elections on fabricated charges. Given Tisza’s current popularity, this would certainly trigger mass protests. Another scenario is that Orbán makes strategic concessions to the EU Commission: this however could only come at the price of dismantling the patron-client relations which have buffered his regime, and it is unclear why EU elites would have any incentive to make a side-deal with Orbán if they see Magyar as a more promising alternative - which they do [32].

It is therefore more likely that the NER regime will simply try to buy time until the next elections, sustaining subsidized lending for households even at the cost of deteriorating public finances as the IMF points out [33], while praying for a new surge in global demand for batteries and EV exports. Portraying Hungarian critics of battery manufacturing as traitors to the nation [34], the NER regime’s communication increasingly sounds like a plea for German capital to shore up the regime [35] - a dark irony for nationalist champions of sovereignty.

**Endnotes**

[1] https://24.hu/belfold/2025/04/10/21-kutatokozpont-tisza-part-fidesz-kozvelemeny-kutatas/

[2] See the works of Gabor Scheiring and Lawrence King on the public health consequences of privatization in post-Socialist Eastern Europe https://www.researchgate.net/publication/377279049_The_political_economy_of_the_postsocialist_mortality_crisis

[3] For an overview of the household mortgage crisis see the works of Agnes Gagyi and Zsuzsanna Posfai: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372571763_Introduction_boom_crisis_and_politics_of_Swiss_franc_mortgages_in_Eastern_Europe_comparing_trajectories_of_dependent_financialization_of_housing, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341868720_Household_debt_on_the_peripheries_of_Europe_New_constellations_since_2008

[4] For an overview of statist financialization in Hungary see my work on financial vertical https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/10245294211003274, and Dora Piroska’s work on financial nationalism https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351676204_Financial_Nationalism_and_Democracy_Evaluating_Financial_Nationalism_in_Light_of_Post-Crisis_Theories_of_Financial_Power_in_Hungary

[5] See the work of Dorothee Bohle and Cornel Ban on public debt management: https://research-api.cbs.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/66651152/cornel_ban_et_al_definancialization_financial_repression_and_policy_continuity_in_east_central_europe_acceptedversion.pdf#page=4.17

[8] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384355816_China's_European_Bridgehead

[9] https://merics.org/en/comment/merics-forum-chinese-ev-investments-europe

[10] Vilmos Weiler’s forthcoming article “Akkumulátorgyártás és félperifériás tőkefelhalmozás - miért ilyen fontos a NER-nek az akkumulátorgyártás támogatása?” (Battery Production and Semi-Peripheral Capital Accumulation – Why Is Supporting Battery Production So Important to the NER Regime?) will be published in a Special Issue of Hungarian political economy journal Fordulat in Fall 2025

[11] See the works of Agnes Gagyi, Tamás Gerőcs and Linda Szabó on the longue-duree mediating role of Hungary in global capitalism since WWII: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14747731.2025.2491973#abstract, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/62ab7f2c81773d64db4e11b0/t/663985e809ae3e3511cfe01e/1715045865346/2024.6+-+Hungary%E2%80%99s+reindustrialization-+hedging+geopolitical+conflicts%3F+Gagyi%2C+Gero%CC%8Bcs+and+Szabo%CC%81.pdf

[12] https://www.businessinsider.com/ev-sales-europe-slumping-warning-sign-us-2024-9

[16] See Daniela Gabor and Benjamin Braun’s work here: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09692290.2025.2453504 and Brett Christophers’ latest book here: https://www.versobooks.com/products/3069-the-price-is-wrong?srsltid=AfmBOoo6yiXKrqa-nrduugvESygn5BwEUuOI8IGTQhliC6VWpogMa0O7

[18] https://masfelfok.hu/2024/09/30/hidden-hazards-disinformation-and-waste-in-hungarys-battery-boom/

[19] https://masfelfok.hu/2024/09/30/hidden-hazards-disinformation-and-waste-in-hungarys-battery-boom/

[22] https://hvg.hu/itthon/20250201_Tobb-ezren-tuntettek-az-akkugyarak-ellen-Debrecenben

[23] See the works by Marton Czirfusz, Andrea Elteto and Judit Ricz https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/budapest/20101.pdf, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10758216.2025.2459268

[24] See Andrea Elteto’s work on work safety issues in the battery sector: https://real.mtak.hu/209367/1/3_Tudomanyos_tajekoztato_33534e8d8d.pdf

[26] Precise numbers don’t exist for the entire sector as this is a politically sensitive issue for both the government and employers, but the 10% to 17% share of non-EU workers would be consistent with documented employment trends at individual firms

[27] https://magyarnemzet.hu/belfold/2025/04/gvh-buntetes-bige-laszlo-kartell

[28] https://m.hvg.hu/360/20250227_hvg-portre-posfai-gabor-tisza-part

[30] https://24.hu/belfold/2025/03/05/ruszin-szendi-romulusz-tisza-part-magyar-peter/

[31] https://nepszava.hu/3274917_politika-magyarorszag-fidesz-ellenzek-tuntetes-hadhazy-akos-interju